Full-Court Press: The Strategic Gamble of An NCAA Champion's Media Front Run

A data-based look at LSU coach Kim Mulkey's attempt to preempt the Washington Post. Did it work?

Publisher’s note: 48 hours after I posted this edition, I added a quick update with new data and developments in my notes section. Check it out here.

In the vast playbook of communications strategies, 'front running' stands out to me as particularly fascinating. It’s a preemptive move that involves sharing your version of a story before an impending very damaging article can undermine your organization.

This is a strategy that’s been put to use by the likes of Coinbase, Elon Musk, Meta, Wells Fargo and several other prominent companies and leaders. In a lot of ways, it *should* squarely fit into my own Comms ethos of “proactivity always”. But on the other hand, I have real doubts about its effectiveness in most cases.

So I was intrigued this week when LSU women’s basketball coach Kim Mulkey decided to front run an impending story by Kent Babb of the Washington Post. It’s been big national news in the middle of the biggest tournament of the year. And as of a few hours ago the story just came out. And not surprisingly, it’s rough. It has strong negative sentiment toward Mulkey, with especially low marks related to the narratives “Kim Mulkey treats players and staff well”, “Kim Mulkey is a respected leader”, and “Kim Mulkey is trustworthy”.

"In a lot of ways, front running should squarely fit into my own Comms ethos of 'proactivity always'. But on the other hand, I have real doubts about its effectiveness in most cases."

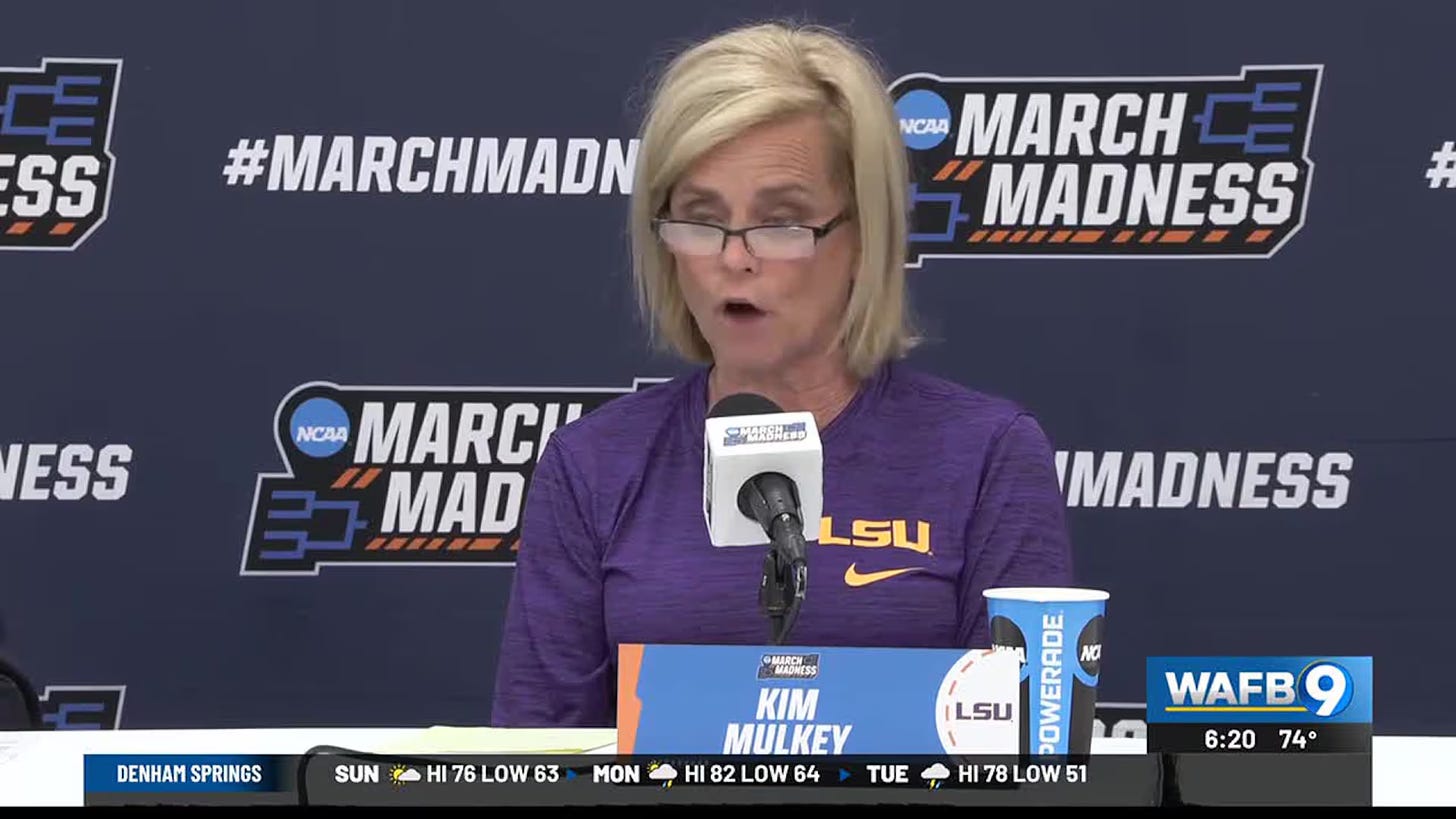

But first, some backstory: In case you’re not familiar with Coach Mulkey, she leads one of the NCAA's truly elite teams. But this isn’t a newsletter about basketball, it’s about Comms. She caught my attention during the opening weekend of the NCAA tournament because she used a team press conference during the opening weekend to head off the story (her comments start at the 18:18 minute mark of this video) labeling the reporter as “sleazy” and denouncing the piece as a clear "hit job." And Coach Mulkey didn't stop there; she also threatened to deploy what she termed "the best defamation law firm in the country" against the publication1. This assertive approach in advance of the story’s publication is quite telling about her approach to shaping the narrative.

To be clear, while I’ve watched her team, I have no personal stake or deep-seated opinions about Coach Mulkey herself or the opinions expressed in the article. At face value, her track record is remarkable, highlighted by winning four NCAA championships. And I personally err toward celebrating anyone that elevates women's sports to be an even more integral part of American culture.

As for Kent Babb of the Washington Post, I wasn’t familiar with his work. So my take is as neutral as it gets2.

But I do know Comms theory and strategy. And this real-time example made me hungry for data to answer a simple question: does front running actually work?

First, What Is The Strategy Of Front Running?

Imagine you catch wind that a journalist is about to drop a bombshell piece that paints you, your executive or your company in a terribly unflattering light. The common path followed by most organizations is to engage in a fierce back and forth with the reporter to assert your side of the story. But at some point that journalist’s reporting is finished and all you can do is sweat bullets and wait for the piece to hit.

But with front running, you take the narrative into your own hands. Tactically, you might release a blog post, hold a press conference, or give an exclusive interview to another outlet, laying out your side of the story before the original piece even hits.

The theory is that front running gives an opportunity to frame the conversation on your terms, potentially softening the blow of the negative coverage.

Some people call front running bold, others call it risky, and many think it stupid or even unethical. Off the top of my head, I see a range of pros and cons:

"The theory is that front running gives an opportunity to frame the conversation on your terms, potentially softening the blow of the negative coverage."

Potential Benefits

Shapes the Narrative: By sharing your version first, you might be able to frame the conversation on your terms.

Demonstrates Transparency: Proactively addressing potential issues can be seen as a sign of transparency and honesty, qualities that build trust with your audience.

Prepares Your Audience: It may soften the impact of the negative coverage by preparing your audience for what's to come, potentially reducing shock and backlash.

Potential Risks

Amplification: You risk drawing more attention to it than it might have otherwise received. Sometimes much more.

Burning Bridges: Want to piss off a reporter and their editor? Front run their story. And - frankly - other journalists are likely to notice too and show solidarity in their anger.

Credibility on the Line: If your preemptive message is perceived as spin or if it contradicts the facts of the subsequent report, your credibility could take a hit.

Timing is Everything: If not timed perfectly, your preemptive strike could either be forgotten by the time the negative story breaks or could be seen as a reactionary rather than a strategic move.

Potential for Backfire: There's always a chance that your attempt to control the narrative could backfire, especially if the reporter or public feels manipulated or misled.

Some people call front running bold, others call it risky,

and many think it stupid or even unethical.

So Does Front Running Work? What Does The Data Say?

Methodology

Using the proprietary AI platform I've developed, I conducted a comprehensive analysis on two sets of 100 articles each sourced from Google News. The first set, aimed at understanding the recent upheaval. The second set focusing coverage in February, provided a baseline to identify sentiment patterns before the recent press storm.

I used both GPT 4.5 and Claude 3 for measuring sentiment and the extent of narrative pull-through in all stories. This dual-model approach allowed for a nuanced understanding of the narratives surrounding Coach Mulkey, laying the groundwork for a thorough exploration of media portrayals before and after this front run strategy was put into action.

The attempt to front run appears to have backfired,

as it drew a LOT of negative attention.

Overall Sentiment

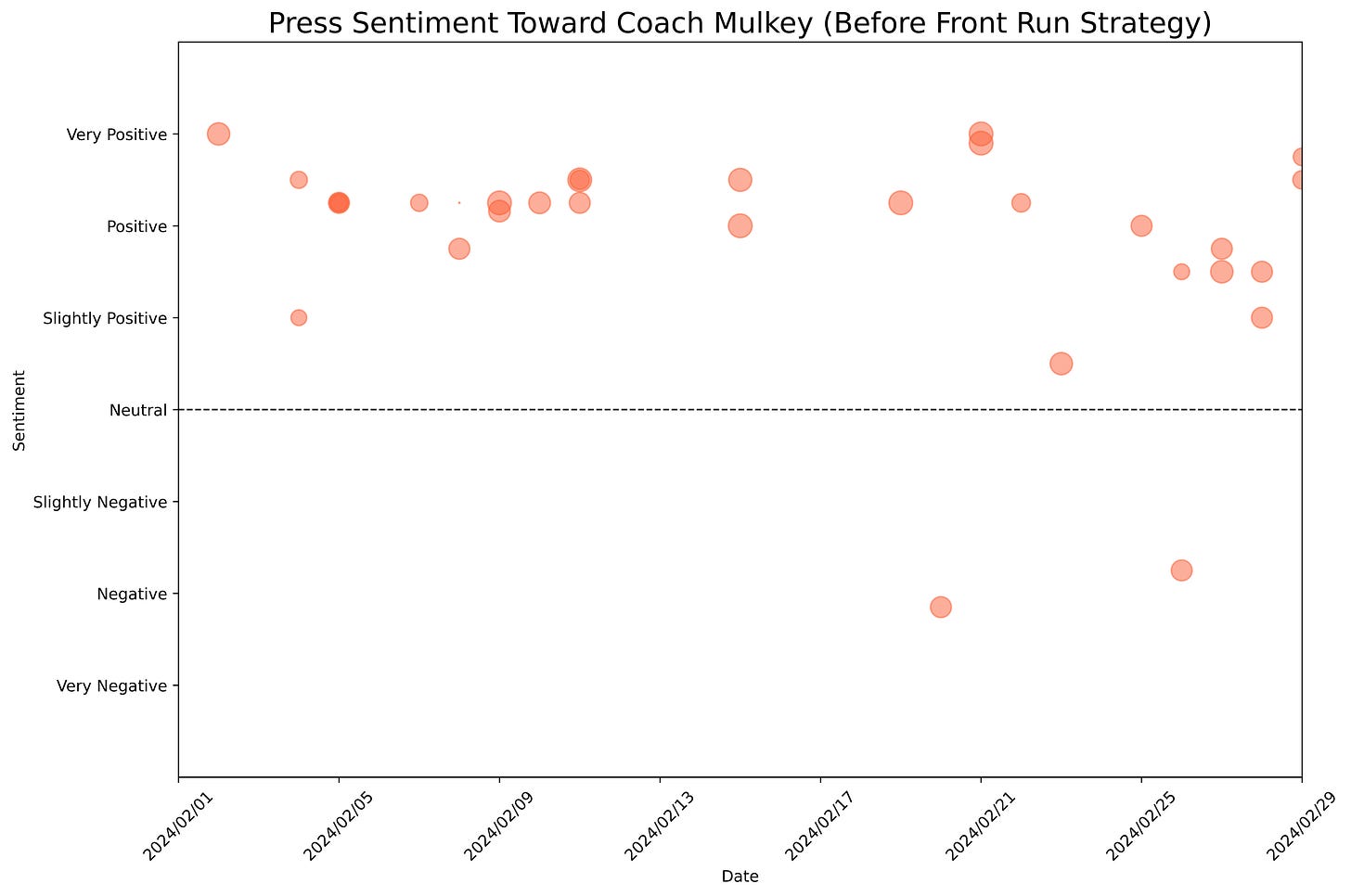

With this framework in place, I started by examining coverage from February, before any of this controversy popped up. Read this footnote3 to get a sense of how to read the charts.

In this “before” snapshot, the media’s portrayal of Coach Mulkey was overwhelmingly positive, reflecting the widespread admiration for her coaching prowess and her team's success. This baseline sentiment aligns with expectations for a celebrated coach at the helm of a winning team. Nothing in this surprised me.

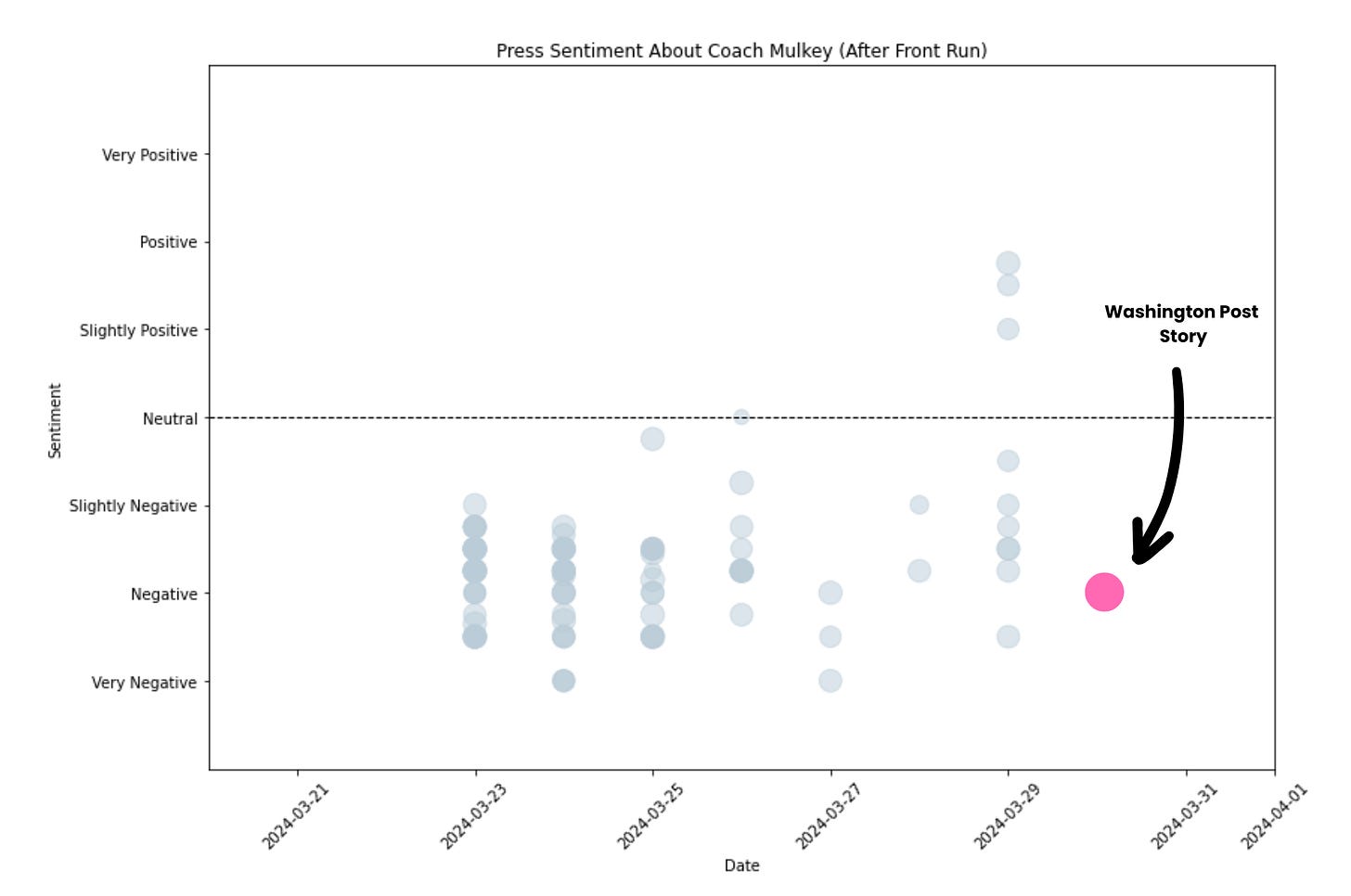

However, sentiment sharply declined immediately after the coach's preemptive response to the Washington Post article.

Even before the Washington Post's story was published, an overwhelming 89% of related stories cast her in a negative light, with nearly all of them focusing on the controversy stirred by the front run. This resulted in more than 100 articles, many in highly prestigious outlets, all honing in on Coach Mulkey with a predominantly negative slant. From this perspective, the attempt to front run appears to have backfired, as it drew a LOT of negative attention.

Narrative-Specific Analysis

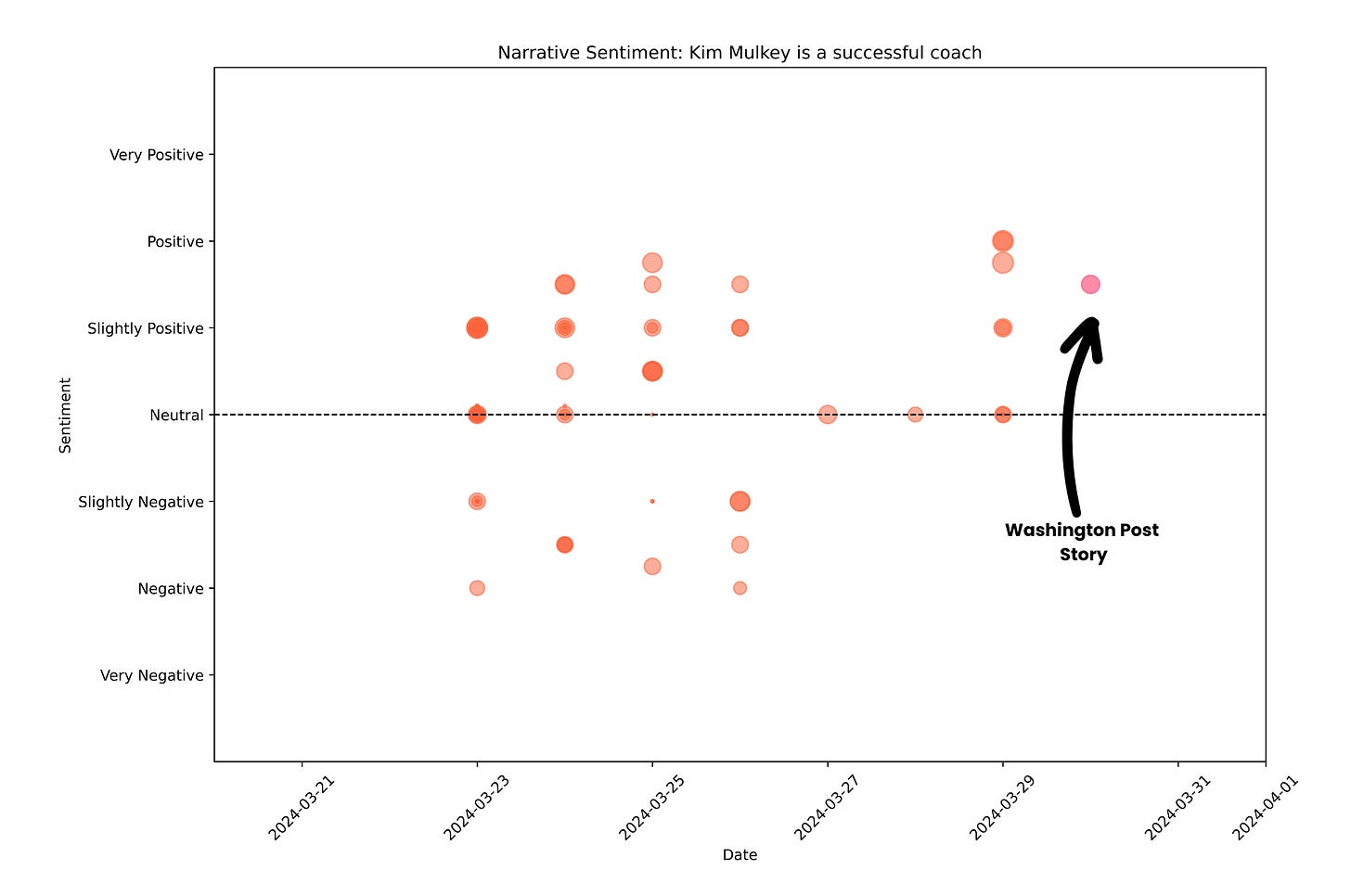

But here’s where things got really interesting to me: I also analyzed each story for pull through of four different narratives. Click on this4 footnote for a quick primer on how to read these specific charts.

Success as a Coach: Despite the overarching negative sentiment, 46% of the coverage credited Coach Mulkey's success on the court, acknowledging her impressive record. This was fully expected given her history of on court achievement.

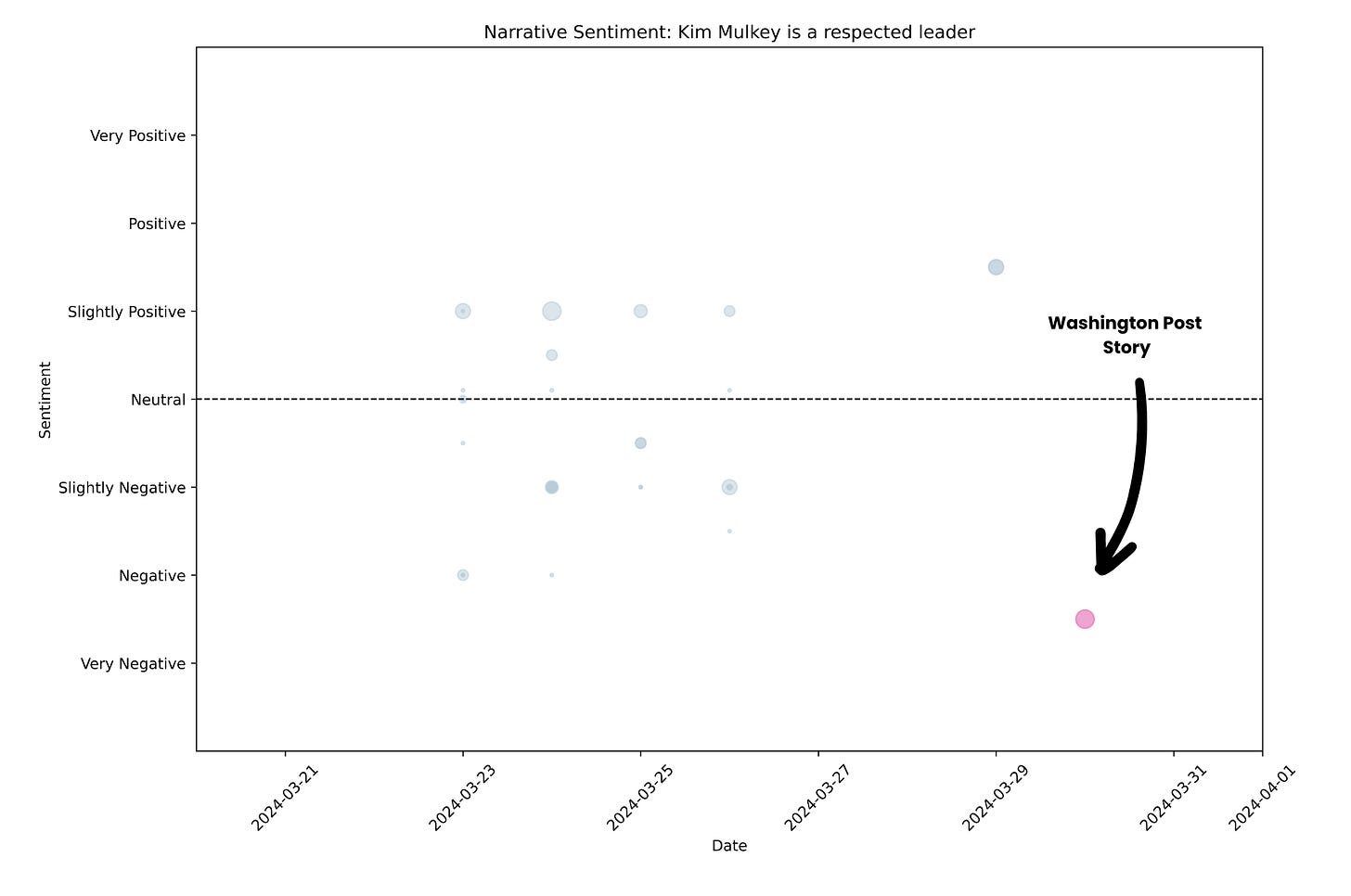

Respected Leader: When analyzing coverage for reflections of Coach Mulkey as a respected leader, the sentiment was more negative (33% positive vs. 58% negative, with 9% neutral). Importantly, most bubbles were very small, suggesting that this narrative had limited pull through in the overall coverage.

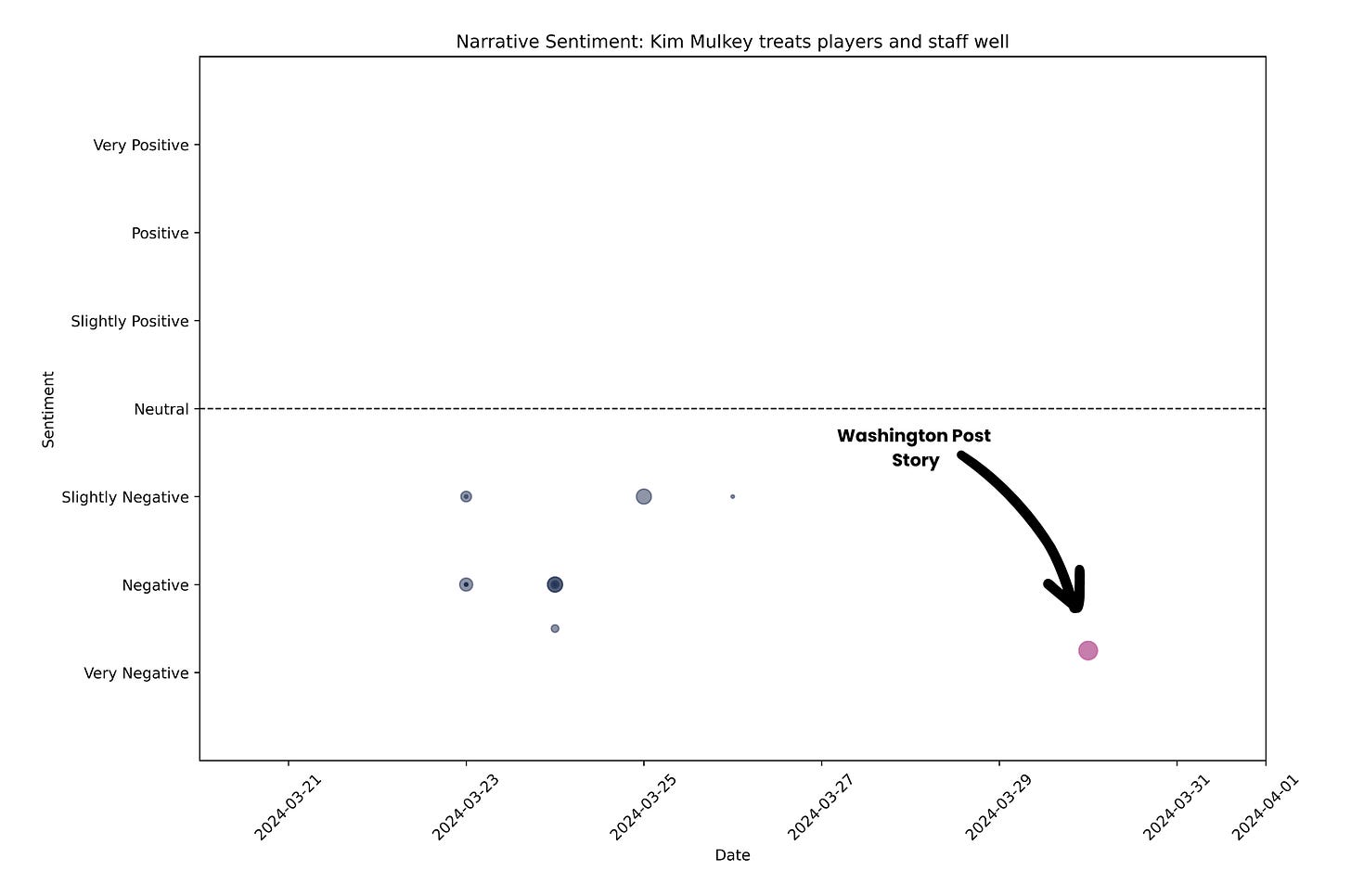

Treatment of Players and Staff: The narrative regarding how Coach Mulkey treats her players and staff showed a very slight negative bias. However, in fairness, the narrative was not dominant at all, as indicated by the relatively small size of the bubbles.

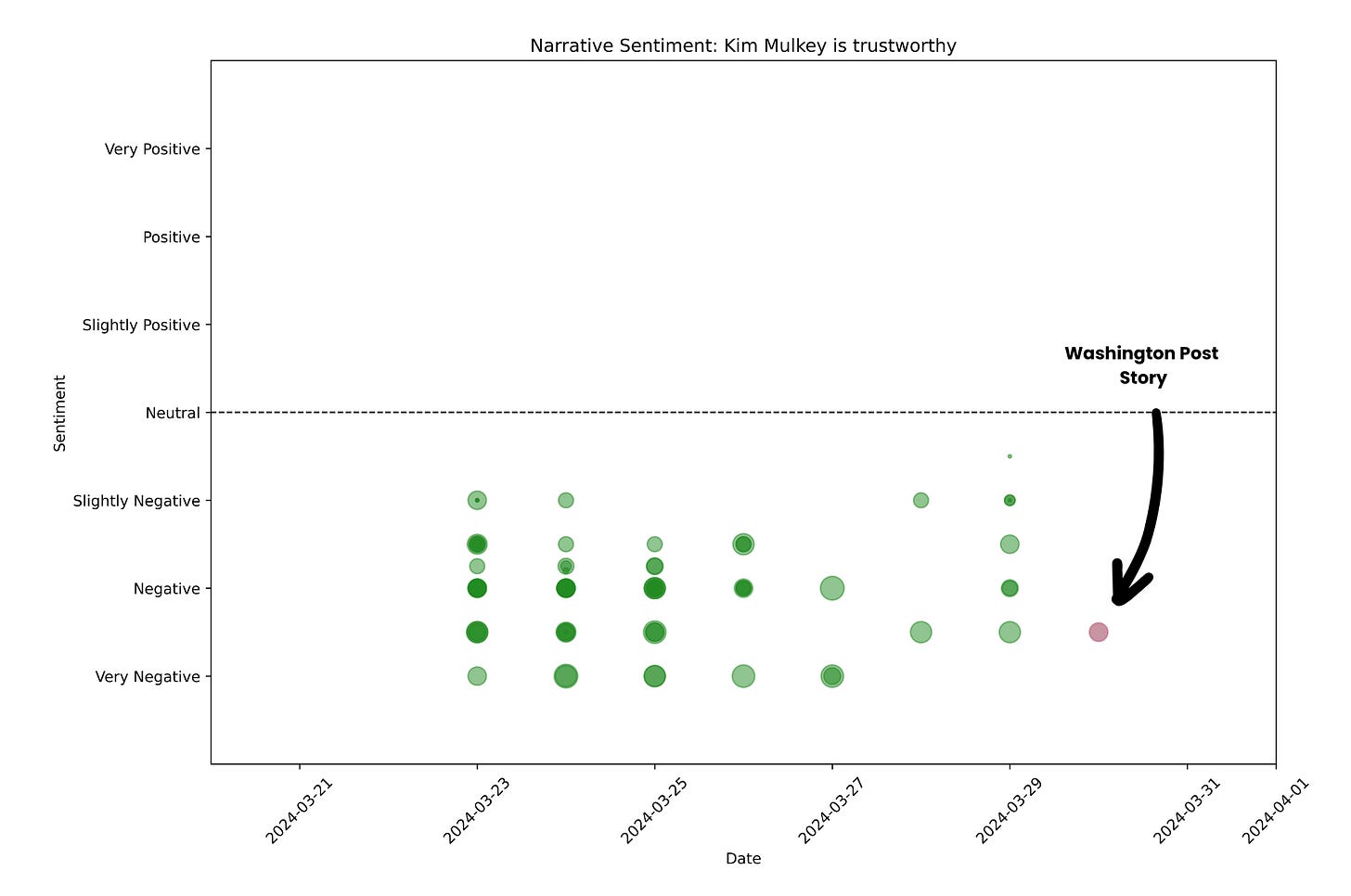

Trustworthiness: The most detrimental finding was that 100% of the articles touching on Coach Mulkey’s front run cast her trustworthiness in a negative light, with several large bubbles indicating a significant emphasis on this narrative.

To me, of all the findings in this analysis, this chart is probably the most powerful evidence that the attempt to preempt the Washington Post story probably wasn’t successful. Its rare to see somebody who is typically so admired take such a hit on trustworthiness.

My Own Thoughts 💭

After analyzing the data, it seems clear that Coach Mulkey’s attempt at front running probably hasn’t panned out as hoped. At least, not so far. The strategy has drawn considerable negative attention, and it doesn't appear to be steering the conversation in the intended direction.

I do think the timing of the story is absolutely terrible, bordering on cruel. It was basically timed to hit as the team started playing their Sweet 16 game today. What a terrible distraction for the players. The squad does not deserve this (but they did win the game).

There are also a few unknowns worth acknowledging:

Did Coach Mulkey’s Strategy Alter the Washington Post’s Coverage? Is there a possibility that her preemptive strike might’ve influenced the narrative? It doesn’t appear it did. From my read, the article didn’t pull any punches.

The Hypothetical “What If”: It’s intriguing yet completely speculative to consider what the outcome might have been if the Washington Post story was published without Mulkey’s front-running attempt. Is the final story so damaging and generated so much follow-up coverage and public interest that it’d justify creating 100+ highly negative articles with a front run? Would it have even registered on my radar or that of the broader audience? Predicting such ripple effects is nearly impossible

A Hidden Objective? Maybe there’s a more specific goal behind Coach Mulkey’s strategy that’s not immediately apparent to outsiders. While my analysis focuses on general public sentiment, she might have been aiming at a more targeted objective, such as safeguarding the commitment of her incoming recruiting class. And maybe she was willing to weather a storm of negative sentiment to secure that objective. Again, this is completely speculative on my part, but such strategic decisions happen and are typically well-considered.

The Role Of Gender: I also have to acknowledge that gender stereotypes could play a role here. All of the past examples of front running I pointed to at the beginning of this article were led by powerful men. I’ve been thinking about how to factor gender into this analysis and cut out as much bias as possible, but don’t have an answer. However, I will say that anecdotally, my sense is that all the previous examples I cited led by males fell similarly flat. I’ll keep my eye on this angle for future explorations of front running (trust me, this won’t be my last).

So where does all of this leave me? This deep dive into front running has been more than just intriguing; it's squarely challenged my guiding mantra of “Proactivity Always.” For years my communications ethos has been arguing for the power of always taking the initiative. On paper, front running embodies this philosophy at its most extreme—a strategy I should, by all accounts, love.

Yet, I find myself not loving it. In practice, examples of front running that genuinely hit the mark are few and far between. And this initial data analysis only underscores my skepticism, suggesting that while the idea of front running theoretically aligns with my beliefs in concept, its execution falls short. I’m still thinking this through.

This deep dive into front running has been more than just intriguing; it's squarely challenged my guiding mantra of 'Proactivity Always.'

Which brings me to a broader question: What is the best course of action in situations like these? I'm eager to hear your thoughts. Is the risk of front running, with its uncertain outcomes and potential for backlash, worth the attempt to control the narrative? Or does this strategy often do more harm than good? Let me know what you think.

Will

Publisher, The Repute

Founder and Principal, Valentine Advisors

will@valentine-advisors.com

If you watch the video you’ll see Coach Mulkey ground much of her defense in disappointment with a past article by Babb about LSU and former football head coach Brian Kelly that focused on the disparity between his high pay and the surrounding community. I analyzed that story and it was rough. Coach Kelly scored negatively on overall sentiment overall in the piece.

Yes, I’m neutral on Babb and the Washington Post, but I get where folks are coming from when they say they’ve been hit by an unfair piece. Been there myself a few times, and it sucks. It’s just part of the game, unfortunately, and it really gets to you and your senior executives emotionally when you’re on the receiving end.

Here is a quick primer to read the two Overall Sentiment Analysis charts: we queried each article with a simple question: “how does the average informed reader feel about Coach Mulkey after reading this article?”

Left Axis (Sentiment): High positions indicate positive sentiment towards the company, while low positions indicate negative sentiment.

Bottom Axis (Date Range): This axis displays the timeframe of the analysis, showing how sentiment has changed over specific dates.

Bubble Size: The size of the bubble reflects the company's prominence in the story. Larger bubbles mean the company is more central to the story.

Bubble Shading: You may notice darker bubbles, which result from high concentration of stories sharing similar sentiment.

These charts offer a visual snapshot of the company's portrayal over time, combining sentiment analysis with how prominently the company figures in media stories.

And here is a quick primer to read the 4 Narrative charts: Each article is evaluated to determine how prominently a specific narrative is featured. And then that same narrative within each story is scored for sentiment, reflecting a positive or negative portrayal.

Left Axis (Sentiment): Higher positions indicate positive sentiment; lower positions indicate negative sentiment.

Bottom Axis (Date Range): Shows the period over which the narratives were analyzed.

Bubble Size: Represents the narrative's prominence in a story. Larger bubbles indicate a more significant focus on the narrative.

Bubble Shading: You may notice darker bubbles, which result from high concentration of stories sharing similar sentiment.

A Note Re Multiple Narratives: A single story may contain multiple narratives, hence an article can appear in more than one chart if different themes are being analyzed.